Lucky for us, bonyi don’t care whether they are art or not…..

Munimba-ja—a Jinibara word for ‘welcome place’, is situated on the second busiest street in the small, rural Queensland town of Maleny. Its boundaries are demarcated by the cyclone fencing of its urban allotment, shared with a boutique native plant nursery that occupies the lower level of its colonially-inspired, worn and wooden ‘Queenslander’ building. Inside, a gift shop, like an eclectic repository of past projects and local connections: paintings, prints, found stone tools, hand-made artefacts, printed cushions and political t-shirts; a small white-walled room complete with gallery lighting and hanging systems; a simple kitchen for tea-making; and a back veranda with table and chairs, overlooking the deep rows of nursery plants, and busy customers below. All of the wooden walls and floors and railings showing the idiosyncrasies of use, and hold the warmed and aged smells and feelings of human time and habitation. Outside, two juvenile bonyi/bunya trees sit in pots on the front porch; and a small dance circle and smoking place, fits snugly amongst the overhanging trees gravilias and wattles, the imported sand spilling over into the carpark asphalt. All manner of native plants are dotted in and around the edges. One in particular, a stink bush, emits a pungent and familiar smell for me, growing up in South East Queensland. Squeezed in between a pallet of plastic-wrapped garden mulch and a shade house, a disturbed rectangle of earth, belies past community meals, or kupmurri (djarala djarlo tjidgen) cooked beneath the ground. A simple red and black graphic sign with the name Munimba-ja, along with two hand-drawn fire sticks, adorns the facade, and signals, within visual vernacular, its role and purpose as ‘art and cultural space’. As if every inch of Jinibara, wasn’t already a space of art and cultural production.

In a broader and more culturally-centred reality, Munimba-ja is a space, within a space, within a space, geographically and culturally located on the eastern edge of Jinibara Country—a contextual, multilingual and integrated Aboriginal nation-sovereignty, with its own unique function and purpose within a fluid and diverse, diplomatic culture-scape. The relatively recent determination of Jinibara Native Title within the area, by some other government and logic, lands like awkward and contentious mark-making, still reverberating within what was once a very different way of collective understanding, respecting and belonging to place. A now fixed and flattened cartography, foreign and impermeable, lines in the sand. Central to the maintenance of customary, relational sovereignty were large-scale, seasonal food events like the multi-national bonyi/bunya gathering, of which Jinibara, as part-host, played an integral part. Bonyi gatherings were attended by tens of thousands of people from far reaching nations, cultures and languages, including Gamilaroi, happening in the region since time immemorial, and ceasing only under the relatively recent pressures of extreme colonial violence. Stories within my circles alone, of settlers at the edges of ‘properties’, armed and waiting to shoot dead those, young and old, travelling along the well-worn and established tracks of connection. Along the pathways to the bonyi gathering, groups would stop and perform ceremony, including rites of passage, exchange gifts with local peoples at each tribal boarder, and await permission, invitation, guidance and acceptance into both a geographic and cultural landscape. Boarders maintained with respect and intelligence. Boundaries, while porous and interwoven, having structure made by Lore, the law of the land—the logic of creation, generation, collectivity and reciprocal care. A co-curated, collaboration with Country. Like all ‘art and culture’ spaces, Munimba-ja is curated to the human scale, of place/time moments, of conceptual ideas, of learning and exchange. And now, with the overarching mindfulness of western art institutional tropes, expectations, needs and values.

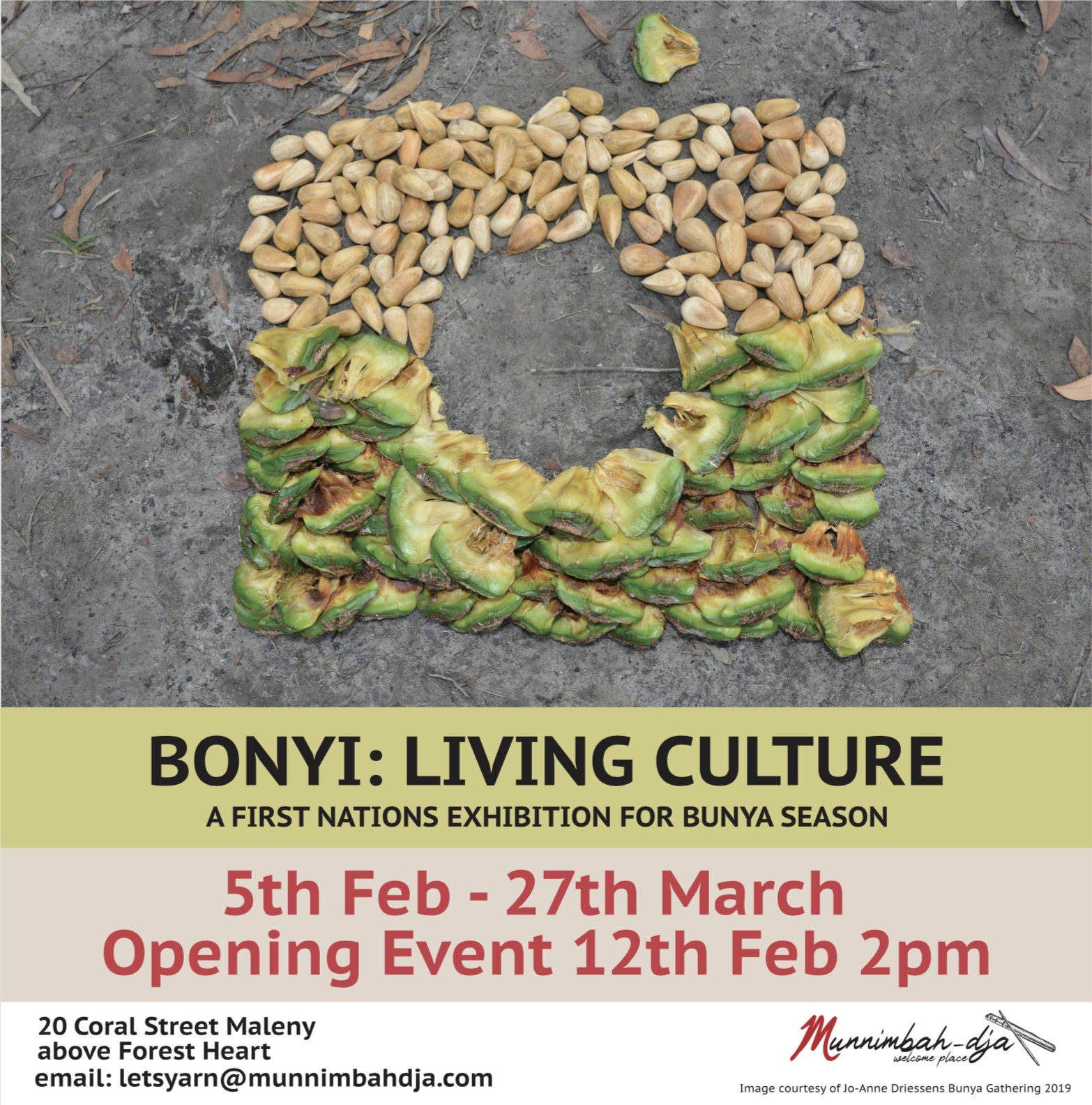

Lucky for all of us, bonyi, or bunya nuts, don’t really care whether they are art or not. Over the duration of the 2022 bonyi fruiting season—which coincidently was a ‘bumper’, and very generous year in its mast fruiting cycles, Munimba-ja played host to the Bonyi: Living Culture exhibition, curated by Quandamooka artist Libby Harward and myself, and in consultation with Jinibara man, BJ Murphy. The event brought together eight contemporary Aboriginal artists (Aunty Beverly Hand (Kabbi Kabbi/Gubbi Gubbi), Kieron Anderson (Quandamooka and Jinibara), Shannon Brett (Wakka Wakka, Butchulla and Gurang Gurang), Jo-Anne Driessens (Wakka Wakka and Kalkadoon), BJ Murphy, Libby Harward and myself—all with ancestral connections to the bonyi gatherings, in a performative place/time moment of collaboration, connection-making and cultural continuum. During the exhibition were also scheduled talks, workshops, shared meals and other events.

For the weeks prior, the energy and excitement of the fruiting bonyi was palpable, generating movement, connection and conversation both locally and within the region. My first ‘bumper’ season on Jinibara Country, I was constantly scanning the horizon for the gentle, firecracker-like tops of the bonyi, taking detours and stopping to collect fallen cones by the side of the road, and or making the effort to visit and share the harvest with friends and family. Most mornings my son and I would shuck cones, and examine and sort the growing piles of nuts covering the loungeroom floor. Over time the nuts and cones changed, hardening, softening, and or rotting over time and conditions, and we experimented with the best times to eat, and methods of cooking. While our old people would have known all about the bonyi, we were still very much beginning our remembering. For months, most family meals included bonyi in some form. Like our loungeroom, the sand dance circle of Munimba-ja became a large stockpile of bonyi cones—with an open invitation for the broader community to share in both bonyi and culture. Whenever I visited, the space was full of new faces, shelling and eating freshly cooked nuts. The smell of roasting bonyi from a small, portable toaster oven, a constant background presence within the gallery. Numerous pairs of garden secateurs, used to wrestle and crack open the hard nut shells, sprawled casually across benches, floors and tables. BJ and Libby took ute-loads of bonyi to neighbouring communities, such as Cherbourg, to family on Minjerribah/Stradbroke Island, and to Invasion Day community rallies on Yuggara and Turrbal Country, in Meanjin/Brisbane. So apparent was the sheer abundance and generosity of the bonyi, and it’s reverberating requirement to share and be generous with others. When bonyi cones hit the ground from the height of their branches, they are woken into activation, effecting and changing the soil as they too are transformed from fruit, into seed, and back into tree.

Oftentimes gallery exhibitions can seem like harsh jolts, or interruptions to the regular flow of life and movement. One day, an empty white container, and the next (*insert a flurry of stress and logistics), a meticulous and perfected—and disconnected, ‘show’. Before the exhibition, Bonyi: Living Culture was already embodied in the environmental and cultural processes activated by the bonyi, happening for at least the last 120,000 years. For nine weeks, all of these happenings and processes, connections and conversations, condensed and partly settled within Munimba-ja. Even still, sculptural installations were continually rearranged, learnings exchanged, and the processes of culture and creation, were unpretentiously, and unashamedly made apparent for anyone to see—who knew how to look. Nothing in the space was entirely ‘finished’, acknowledging its continual and infinite reaching towards both past and present, and another purpose and reason outside of art industry spheres. Like the bonyi gatherings of old, the exhibition was informed and determined—almost curated, by the bonyi, and its physical, seasonal, cultural and relational logic. The way in which the artworks evolved, and curation took place, was an ongoing and organic type of collaboration, based on relationships, trust, and with culture at the centre. All of the works, speaking to each artists’ deep and ongoing connection to bonyi, like Shannon Brett’s cobalt blue and gold/copper bonyi printed caftan; Kieron Anderson’s suspended, floor to ceiling kabul, or carpet python made from used and decaying bonyi shucks; BJ Murphy’s sawn bonyi stump, lovingly covered by a woven, funerary dilli bag; Jo-Anne Driessen’s photographic images documenting the activity of recent bonyi inspired festivals in the region; and Aunty Beverly Hands decorated message sticks, momentary pausing along their journey and purpose to bring people of the bonyi together.

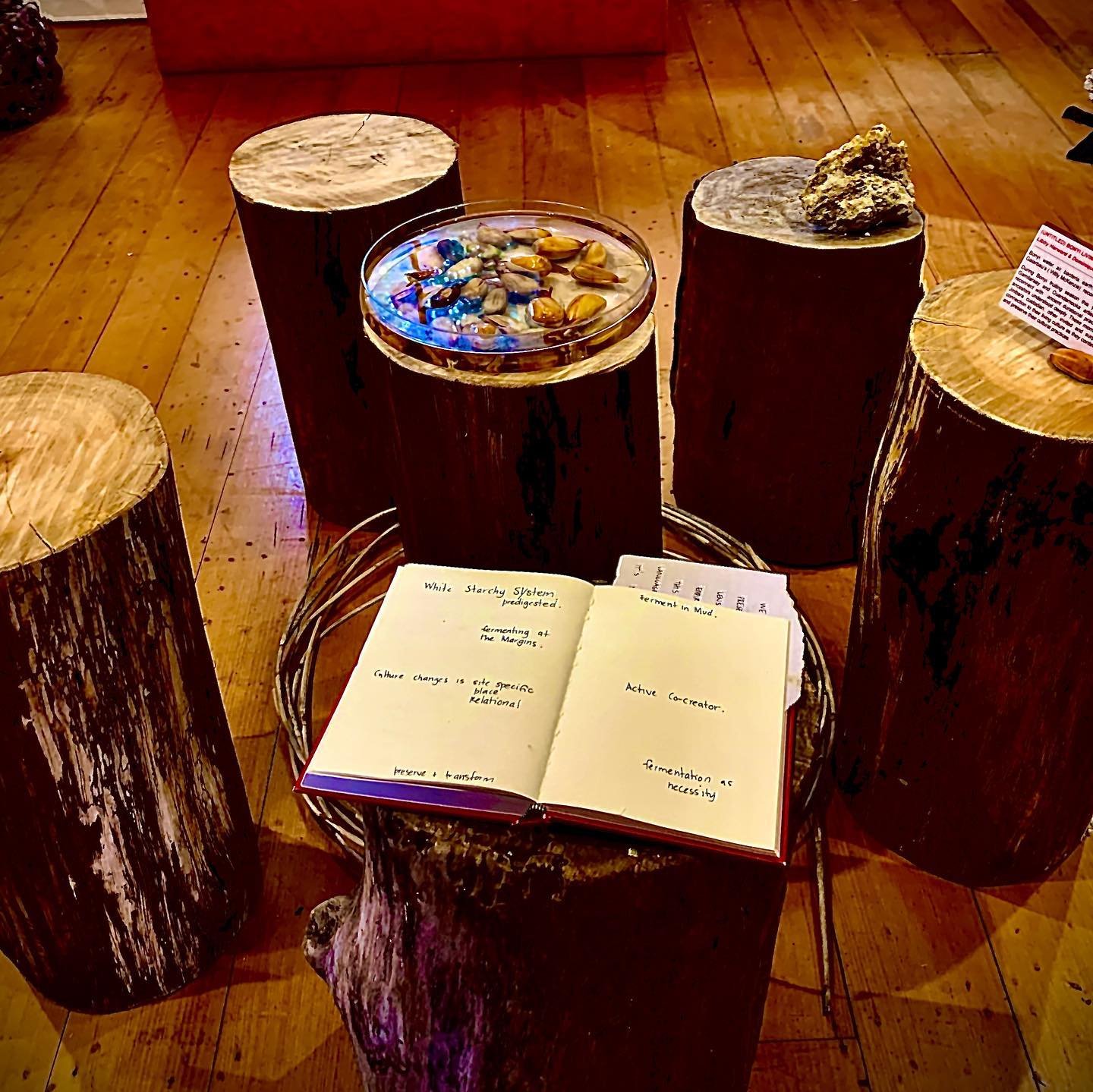

In the center of the gallery space was a round and shallow bowl of fermenting bonyi nuts, that Libby and I framed as our relational work, (Untitled) Bonyi Living Culture. The wide and shallow bowl was placed atop one of several wooden stumps, acting as both plinth and sitting space—an invitation for an unsettled and moving positioning, both ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ the work. At times, and depending on the movement of bodies and the activation of the space, some hand written artist notes, and a small card didactic was placed on or amongst the stumps, reading:

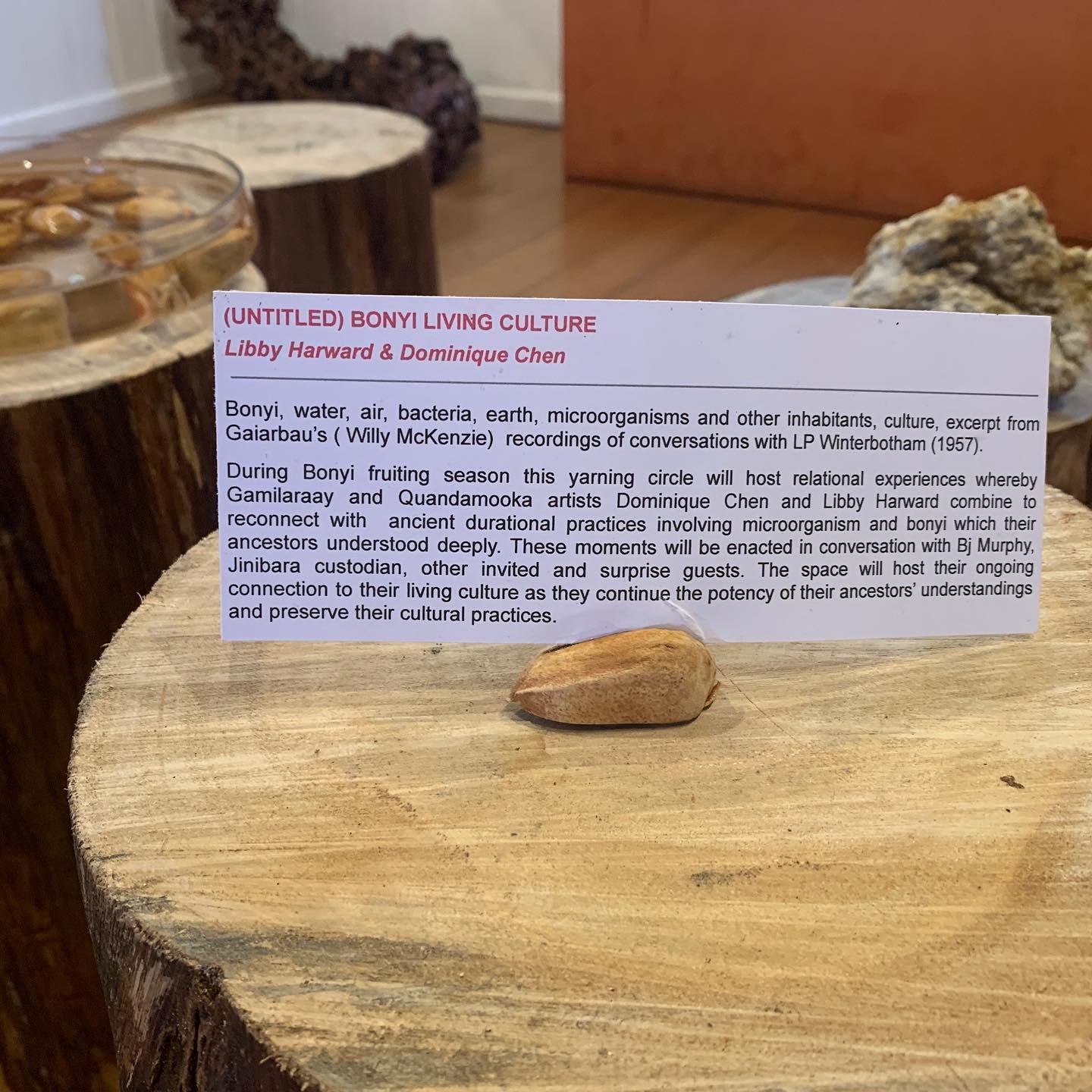

(Untitled) Bonyi Living Culture

Libby Harward & Dominique Chen

Bonyi, water, air, bacteria, earth, microorganisms and other inhabitants, culture, excerpts from Gaiarbau’s (Willy McKenzie) recordings of conversations with LP Winterbotham (1957). During Bonyi fruiting season this yarning circle will host relational experiences whereby Gamilaraay and Quandamooka artists Dominique Chen and Libby Harward combine to reconnect with ancient durational practices involving microorganisms and bonyi which their ancestors understood deeply. These moments will be enacted in conversation with BJ Murphy, Jinibara custodian, and other invited and surprise guests. The space will host their ongoing connection to their living culture as they continue the potency of their ancestors’ understanding and preserve their cultural practices.

Every few days, the water in the ferment was changed, and conversations were had in, around and because of the work. Strong and fizzy ngali/us two talks between Libby and I, in the days and weeks leading up to the public opening, and slowly transforming ngiyani/us, more than two conversations with larger groups from outside our cultural contexts, as we shared as part of the public programming. A bowl of fermenting bonyi, it seems, is an amazingly generous and safe container to speak both metaphorically and literally of culture, in ways that move beyond the specifics of language of one human cultural phenomenology or another. The yarns were flowing and easy, poignant and present. Quietened by the subtle listening/observing space that the fermentation required. Part of the genesis of the work was the reclamation and (re)learning of bonyi fermentation processes, minimally recorded by Jinibara ancestor Gaiarbau (Willy McKenzie). Opening up the space to others, made broader connections and experiences of ferments across cultures, adding to paths of rediscovery and insight. As we talked we listened to the bonyi ferment, here now as very real and visceral, relational collaborator of ‘high cultural’ and ‘creative’ production. Never settling, always generating. While we changed the water, we also changed and revitalised the ferment with our own proximate conversations—the microbial breath of our effervescent and emergent ideas, mingling and morphing their expression, as if they too were listening…and in return, germinating and revitalising our ideas and understandings in the most fundamental of creative exchanges. Patterns of transference, relatable to both the micro and macro realms. Liminal and thinning thresholds of awareness between our selves and the bonyi, and all the other inhabitants, elements and forces continually at play. As the fermentation progressed, the water clouded and the kernels sprouted shoots, like twisting and mingling antenna searching for collaborative signs of life, and with it, a deep understanding that nothing can happen in a vacuum, not even decay. The autonomy of the air/breath, water, bacteria and bonyi, forging and generating new and uncertain spaces—with no preconception, ego, authorship or artistic acclaim. A breath of fresh, cultural air. Wholeheartedly experimental and brave. Like yaama yanay yulugi (interpreted as I dance, you dance, we dance), their relational interaction celebrating each autonomous sovereignty as being necessary to one’s own, opening up the membranic boundaries, and permeable possibilities of an interdependence that creates more than merely consumes. A sum, more than parts. The limitless of the liminal, and a suitable container for cultural growth and continuation.

As the bonyi fermented, the sun moved in and out of the gallery windows, casting beams of light and shadow on the walls, reminding the space of its bigger relational contexts. Exhibition goers came and went in waves, growing and reducing in synch with the major regional flood events happening over the time. The central location of the ferment, as well as its ability to conceptually centralise the transformative in ‘living culture’, created a grounded positionality through which the meaning and interpretation of the ‘peripheral’ works could be continually engaged/re-engaged, and animated from the certainty of their two and three dimensional form. The ferment reminded that nothing in creation is ever really fixed or ‘settled’, and particularly in our cultural contexts, always responding to cultural, physical and societal conditions, interacting and shape-shifting. Just like the ferment, our culture is always relational, and in process, regardless of the snapshot of time/place and flattened dimensionality of art and culture on the gallery’s ‘white walls’, ‘white cubes’ or ‘boxes’. The central location of the wooden seats/plinths of the ferment, reinforced this relational positioning, where one’s ‘view’ was never static or linear, and where an awareness of one’s unavoidable participation ‘within’ the work/s was continually foregrounded. In this sense, the presence of the bonyi, and its ancient logic, kept a kind of accountability within the space. As we, as curators, moved through task lists, debated layouts and had at times, frustrated and uncertain intellectual dialogues with established notions of art and culture within western systems and lenses—worrying about the exhibition’s reception…they were there, engaging in their own, cultural production with vital purpose and reason. Assured, non-coercive and integrating, reminding us of how far removed we perhaps are from the source, and connecting threads of our cultural production within mainstream art systems and values. Spaces that both literally and conceptually, have such limited capacity to hold them.

The moving, creating and decaying fermenting bonyi, and their relational connections—both human and more than human, were a disruption to the art preservation and archival mentality of art institutions, as well as their commodification as Aboriginal ‘cultural capital’. Their seeming ubiquity and mundanity—as food, as seed, as ecology, usually artistically de-valued, but revalued here in this self-determined Aboriginal art and cultural space. Despite the glass container from IKEA, and the wooden walls of colonisation. Like Duchamp’s Fountain, they are the ready-made, or rather, the ready-making. Yet unlike someone’s man-made urinal, their positioning within ‘fine art’ remains tenuous, and perhaps too ‘naturally’ orientated on the western-informed nature/culture divide. In an Aboriginal context, County is culture, and culture is Country…and like it has been, always in this country, because of human participation and activation, as vital, permeable, and willing participant. As co-collaborators in transformative, past and future realities and possibilities. Like Country, and notions of ‘art’, the bonyi ferment required care and attention through mutual presence and relationship—a fine line after all between the outcome of cultural production being health-giving or poisonous. Life-activated or sour. A line we now must walk with strength, patience and attentiveness, as we re-learn and re-make our connections within the cultural milieu—and the spaces within spaces.

© Dominique Chen, 2022.

Dominique Chen is a Gamilaroi yinarr/woman, and interdisciplinary artist and researcher, livining on Yinibara Country in South East Queensland. She lectures within the Batchelor of Contemporary Australian Indigenous Art, Griffith University, and is undertaking PhD research at the University of Technology Sydney, in the area of relational creative practice and urban-based Aboriginal food and medicine growing.